Resolving Ambiguity in Text Rewriting

Text rewriting is the process of replacing parts of a text that matches some rewrite rules with other text. In some cases, however, these parts might overlap so we have to come up with a way to decide which one is to be replaced. In this article, we’ll discuss several conflict resolution strategies and describe their implementations from a formal standpoint.

This article builds on top of Finite-State Transducers for Text-Rewriting so check it out first, before proceeding with this one.

Ambiguity

Consider the following rewrite rule and suppose we have a finite-state transducer for obligatory replacement based on it.

\[ R_1 = ab|bc \to x \]

and the following input text.

\[ aabcb \]

If we don’t specify a conflict resolution strategy, the obligatory rewrite transducer for \(R_1\) will result in two distinct translations because the matches “ab” and “bc” clearly overlap.

\[ a \cdot ab \cdot cb \longmapsto_{R(T_{R_1})} axcb \\ aa \cdot bc \cdot b \longmapsto_{R(T_{R_1})} aaxb \]

Let’s see another example. A rewrite rule

\[ R_2 = aa*b|aa \to x \]

and an input text

\[ aaaaabbaa \]

that results in even more valid decompositions.

\[ aaaaab \cdot b \cdot aa \longmapsto_{R(T_{R_2})} xbx \\ aa \cdot aaab \cdot b \cdot aa \longmapsto_{R(T_{R_2})} xxbx \\ aa \cdot aa \cdot ab \cdot b \cdot aa \longmapsto_{R(T_{R_2})} xxxbx \]

A proper conflict resolution strategy would ensure that for each input text, we’ll get a single output following this strategy.

Definitions

Let’s provide some formal definitions that will make it easier for us to reason about the problem.

Given two strings \( u, v \in \Sigma^* \) we write \( u < v \) if \( u \) is a prefix of \( v \) and \( u \leq v \) if \( u \) is a proper prefix of \( v \).

An infix occurence of an string \( v \) in text \( t \) is a triple \( \langle u, v, w \rangle \) such that \( t = u \cdot v \cdot w \). For example in text \( t = aabcb, \langle a, ab, cb \rangle \) and \( \langle aa, bc, b \rangle \) infix occurrences of the strings “ab” and “bc” respectively.

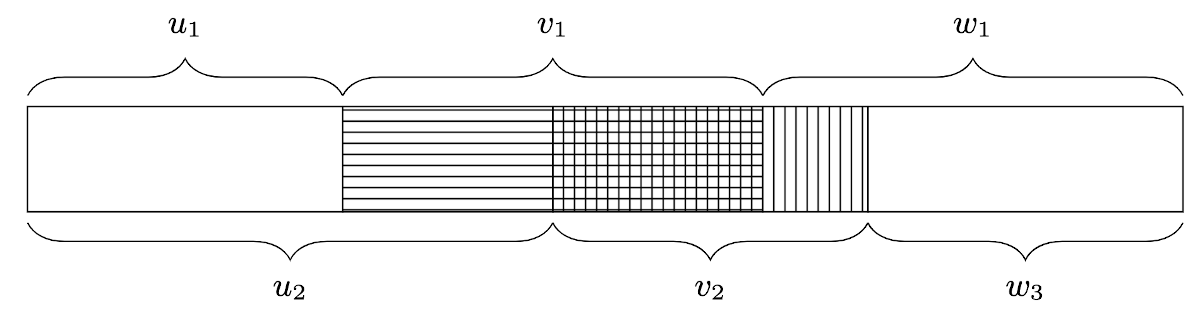

Two infix occurrences \( \langle u_1, v_1, w_1 \rangle \) and \( \langle u_2, v_2, w_2 \rangle \) of a text overlap if \( u_1 < u_2 < u_1 \cdot v_1 \).

Figure 1: Overlapping infix occurrences

A set of infix occurrences \(A\) of the text t is said to be non-overlapping if two distinct infix occurrences of \(A\) never overlap. Let’s see an example.

\[ t = aabbbccab \\ A = \{ \langle a, ab, bbccab \rangle, \langle aabb, bc, cab \rangle, \langle aabbbcc, ab, \epsilon \rangle \} \]

Leftmost-Longest Match

The leftmost-longest match resolution strategy consists of two rules:

- For two overlapping texts, we pick the one that starts first in the natural (left-to-right) reading order.

- For distinct matches starting at the same place, we pick the longest one.

By applying the leftmost-longest strategy in the example above, we get rid of the ambiguity and, thus, end up with the following translations:

\[ aabcb \to_{R^{LML}(T_{R_1})} axcb \\ aaaaabbaa \to_{R^{LML}(T_{R_2})} xbx \]

Formal Description

We’ve developed an intuition for this strategy, let’s define it in formal terms so we can be precise. Given two sets of infix occurrences \(A, B\), we define the following functions:

\[ AFTER(A, B) = \{ \langle u, v, w \rangle \in A | \forall \langle u’, v’, w’ \rangle \in B : u’ \cdot v’ \leq u \land u’ < u \} \]

\( AFTER \) selects from all infix occurrences in \( A \) the ones where the middle component \(v\) starts after all middle components of the set \(B\).

\[ LEFTMOST(A) = \{ \langle u, v, w \rangle \in A | \forall \langle u’, v’, w’ \rangle \in A : u \leq u’ \} \]

\( LEFTMOST \) selects the infix occurrences where the middle components have the leftmost position. Note that we might have multiple such components that start from the same position.

\[ LONGEST(A) = \{ \langle u, v, w \rangle \in A | \forall \langle u’, v’, w’ \rangle \in A : u \neq u’ \lor v’ \leq v \} \]

From the infix occurrences with a middle component starting from the same position, \( LONGEST \) selects the ones with the longest middle part.

Now we can define the function \( LML(A) \) which given a set of infix occurrences is going to return its subset consisting of the leftmost-longest ones.

\[ LML(A) := \bigcup\limits_{i=0}^{\infty} V_{i} \]

Where the intermediate sets \( V_i \) are defined inductively.

\[ V_0 = \emptyset \\ V_{i+1} = V_i \cup LONGEST(LEFTMOST(AFTER(A,V_i))) \]

\( LML(A) \) is always finite because \( A \) is finite. That is, after a certain induction step \( i, V_i \) will remain unchanged and that’s when we break from the loop. At each step, we add at most one element to the resulting set.

Note that also all the infix occurrences in \( LML(A) \) are non-overlapping which leads to another useful property, that is, given a rewrite function \( T: \Sigma^+ \to \Sigma^* \) the obligatory rewrite relation \( R^{LML}(T) \) under the leftmost-longest match strategy is also a function. That is, because our replacement candidates don’t overlap, we rewrite distinct regions in the input text. The original rewrite transducer representing a function means that we do not have the same rule mapping to more than one distinct outputs (e.g. \(ab \to x, ab \to y\)). This guarantees that given any input text, the obligatory rewrite transducer for leftmost-longest match \( T_{R^{LML}(T)} \) is always going to produce a single output.

Other Conflict Resolution Strategies

Now we’ve defined the leftmost-longest match, it is trivial to modify the algorithm to obtain different replacement strategies. For example, for leftmost-shortest, we can replace the \(LONGEST\) function with

\[ SHORTEST(A) = \{ \langle u, v, w \rangle \in A | \forall \langle u’, v’, w’ \rangle \in A : u \neq u’ \lor v \leq v’ \} \]

We can also pick the rightmost out of several overlapping infix occurrences by replacing \(LEFTMOST\) with

\[ RIGHTMOST(A) = \{ \langle u, v, w \rangle \in A | \forall \langle u’, v’, w’ \rangle \in A : u’ \leq u \} \]

By combining those functions, we can define any strategy we want, however, from now on, we’ll focus on the leftmost-longest as it is more applicable in practice. Most of the time, the reading order is from left to right and longer occurrences carry in general more information than the shorter ones.

Conclusion

In this article, we discussed the problem of having overlapping replacement candidates in text rewriting. We defined the leftmost-longest match strategy for resolving such conflicts and learned how to implement it from a formal standpoint. By performing small modifications, we saw how to formally define other kinds of strategies like the leftmost-shortest, rightmost-longest, etc.

The problem for implementing a finite-state transducer, corresponding to the rewrite relation \( R^{LML} \) is already well explored. In the references you can find a few papers providing implementations which differ in complexity and performance.

Part 1: Finite-State Transducers for Text Rewriting

References and Further Reading

- Implementation of a Subsetequential Transducer for Dictionary-Based Text Rewriting

- “Finite State Techniques - Automata, Transducers and Bimachines” by Mihov & Schulz Chapter 11.4 - Regular relations for left-most-longest match rewriting

- “Regular Models for Phonological Rule Systems” by Kaplan & Kay

- “Directed Replacement” by Karttunnen

- “The Replace Operator” by Karttunnen

- “Transducers from Rewrite Rules with Backreferences” by Gerdemann & van Noord