Finite-State Transducers for Text Rewriting

Text rewriting is a programming task when parts of a given input string are replaced with other strings. Applications of this process include text highlighting, annotation, lexical analysis, normalization, etc. Because such tasks arise quite often in practice, many programming languages provide built-in text rewriting APIs. Those APIs, however, often go beyond the realm of regular languages, but rewriters based on regular expressions are still very powerful and can to solve most of the translation tasks that occur in practice.

In this article, we’ll describe the process of text rewriting from a set-theoretic perspective and define the relevant formalisms. We’ll see how they can be applied to implement powerful text rewrites that replace the matching parts of the input string in a single scan.

Formal Preliminaries

Let’s introduce some definitions before proceeding to the main part.

Finite Automata

A finite-state automaton (FSA) is an abstract device that has states and transitions between those states. It’s always in one of its states and while it reads an input, it switches from state to state. Think of it as a directed graph. A state machine has no memory, that is, it does not keep track of the previous states it has been in. It only knows its current state. If there’s no transition on a given input, the machine terminates.

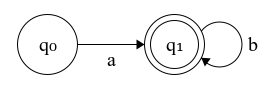

Figure 1: Finite automaton for the expression ab*

Formally we denote FSA as a 5-tuple \( A = \langle \Sigma, Q, I, F, \Delta \rangle \) where

- \( \Sigma \) is a finite set of symbols (alphabet)

- \( Q \) is a set of states

- \( I \subseteq Q \) is a set of initial states

- \( F \subseteq Q \) is a set of final (accepting) states

- \( \Delta \subseteq Q \times \Sigma \to 2^Q \) is a transition relation

The transition relation means that from a given state on a symbol from the alphabet we transition into a set of states (non-determinism). FSAs are used for recognizing patterns in text. For example, the machine in Figure 1 recognizes strings that start with an ‘a’ and are followed by an arbitrary number of ‘b’s.

We denote the empty string as \( \epsilon \) and \( \Sigma^* \) as the set of all words over an alphabet \( \Sigma \). For example, for \( \Sigma = \{ a,b \} \)

\[ \Sigma^* = \{ \epsilon, a, b, ab, aa, bb, ba, aab, bab … \} \]

The language of an FSA \(A\), denoted as \(L(A)\), is the set of all strings recognized by the automaton. The language of the automaton in Figure 1 is:

\[ L(A) = \{ a, ab, abb, abbb, abbbb … \} \]

If a language can be recognized by a finite automaton then there’s is a corresponding regular expression that denotes the same language and vice versa (Kleene’s Theorem). The regular expression for the FSA in Figure 1 is ab*.

String Relations

A binary string relation \( R \subseteq \Sigma^* \times \Sigma^* \) is a set of word tuples over some alphabet \( \Sigma \). For example

\[ R := \{ \langle a, xy \rangle, \langle ab, z \rangle, \langle ab, xy \rangle, \langle abbb, xy \rangle \} \]

is a binary string relation. If for each string of \(R\)’s domain we have exactly one output, then \(R\) is a function. We denote concatenation of word tuples with \( \cdot \) being the string concatenation operator:

\[ \langle u_1, u_2 \rangle \cdot \langle \epsilon, \epsilon \rangle := \langle u_1, u_2 \rangle \] \[ \langle u_1, u_2 \rangle \cdot \langle v_1, v_2 \rangle := \langle u_1 \cdot v_1, u_2 \cdot v_2 \rangle \]

and the concatenation of binary string relations \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) as

\[ R_1 \cdot R_2 := \{ \bar{u} \cdot \bar{v} | \bar{u} \in R_1, \bar{v} \in R_2 \} \]

where \( \bar{u} \) and \( \bar{v} \) are word tuples. Let’s see an example.

\[ R_1 := \{ \langle ab, d \rangle, \langle bc, d \rangle \} \\ R_2 := \{ \langle xy, zzz \rangle, \langle y, x \rangle \} \\ R_1 \cdot R_2 := \{ \langle abxy, dzzz \rangle, \langle bcxy, dzzz \rangle, \langle aby, dx \rangle, \langle bcy, dx \rangle \} \]

Finite-State Transducers (FST)

FSTs are automata with two tapes, namely input, and output tapes. The only difference with FSAs is that when FSTs transition to a state from a given input symbol, they also perform an output. FSAs recognize strings whereas FSTs recognize tuples of strings.

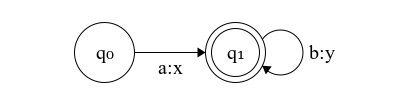

Figure 2: Finite-state transducer translating words in ab* to words in xy*

Formally an FST \(T\) is a 5-tuple \( T = \langle \Sigma \times \Gamma, Q, I, F, \Delta \rangle \) where the transition relation \( \Delta \subseteq Q \times (\Sigma \times \Gamma) \times Q \) and \( \Sigma \) and \( \Gamma \) are the input and output alphabets respectively.

The FST in Figure 2 replaces the input symbol ‘a’ with ‘x’ and ‘b’ with ‘y’. The alphabet of the first (input) tape is \( \Sigma = \{ a, b \} \) and of the second (output) tape is \( \Gamma = \{ x, y \} \). If we discard, we’ll end up with an FSA, equivalent to the one in Figure 1. The transducer performs the following mapping:

\[ a \longmapsto_T x \\ ab \longmapsto_T xy \\ abb \longmapsto_T xyy \\ … \]

The domain of the transducer on Figure 2 is the set of word recognized by the underlying automaton on the first tape

\[ dom(T) = \{ a, ab, abb, abbb, … \} \]

A binary regular string relation is a set of word tuples \( R \subseteq L_1 \times L_2 \) where \( L_1 \) and \( L_2 \) are regular languages. For example, if we have the regular languages ab* and xy|z we can define the regular relation

\[ R := \{ \langle a, xy \rangle, \langle ab, z \rangle, \langle ab, xy \rangle, \langle abbb, xy \rangle \} \]

The binary regular string relations are exactly the relations accepted by finite-state transducers, that is, for each regular string relation, we can build a corresponding FST with its language being exactly this relation.

Text Rewriting

Now we switch our attention towards text rewriting and namely how to express it from a set-theoretic perspective. This idea is introduced in the paper “Regular Models for Phonological Rule Systems” by Kaplan & Kay which you can find in the references below.

Simple Rewrite Rules

A text rewriter contains a finite set of rewrite rules in the form

\[ E \to \beta \]

where \(E\) is a regular expression and \( \beta \) is a word. During the scan, when the rewriter recognizes a string from the language of \(E\), it replaces it with \( \beta \). We can represent a rewrite rule as a regular relation and thus we can build a corresponding finite-state transducer. Let’s see an example.

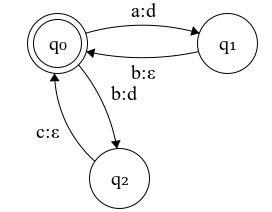

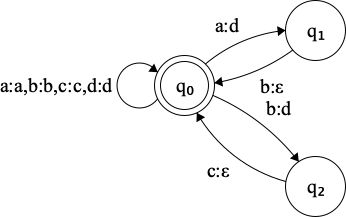

Figure 3.1: FST for the rewrite rule ab|bc -> d

The transducer of Figure 3.1 represents the rewrite rule \( ab|bc \to d \) which is equivalent to the regular function \( \{ \langle ab, d \rangle, \langle bc, d \rangle \} \)

Optional and Obligatory Rewrite Rules

The FST from Figure 3.1 serves of a little practical use because it translates exactly the words in the function’s domain \( \{ ab, bc \} \). We want to build a transducer such that it would work on arbitrary texts and translate multiple occurrences of words in this domain. Consider the text

\[ abacbcaab \]

now let’s underline the replacement candidates, according to the rewrite rule \( ab|bc \to d \)

\[ \underline{ab}ac\underline{bc}a\underline{ab} \]

We want to build a transducer that can process this text and apply the rewrite rule by producing the following output

\[ dacdad \]

We can partition the input text into segments:

\[ u_0 \cdot v_1 \cdot u_1 \cdot v_2 \cdot u_2 \cdots v_n \cdot u_n \]

such that the \(v_i\)’s belong to the domain of the transducer (in our case \( dom(T) = \{ ab, bc \} \)). The \(u_i\)’s are arbitrary strings from \( \Sigma^* \setminus dom(T) \) and for those strings, we want them to be appended to the output as they are. Before we formalize this procedure, let’s introduce the identity function on a set of strings.

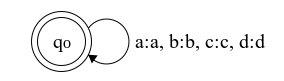

\[ \Sigma = \{ a,b,c,d \} \] \[ Id(\Sigma^) = \{ \langle \epsilon, \epsilon \rangle, \langle a,a \rangle, \langle b,b \rangle, \langle c,c \rangle, \langle d,d \rangle \}^ \]

Intuitively \( Id(\Sigma^) \) is the set of all possible same string tuples over the alphabet \(\Sigma\). For example, the tuples \( \langle ac, ac \rangle, \langle cccd, cccd \rangle, \langle dba, dba \rangle \) are all in \( Id(\Sigma^) \).

Figure 3.2: FST for Id({a,b,c,d}*)

Now we’re ready to define the optional regular rewrite relation \(R^{opt}(T)\) induced by \(T\) for the rewrite rule \(ab|bc \to d\).

\[ R^{opt}(T) := Id(\Sigma^) \cdot (T \cdot Id(\Sigma^))^* \]

Since in the above expression \(T\) is surrounded by expressions \( Id(\Sigma^) \), any substring of a text \(t \in dom(T)\) can be replaced by its \(T\)-translations using \(R^{opt}(T)\). The final asterisk in the definition of \(R^{opt}(T)\) ensures that any number of substrings from \(dom(T)\) can be translated. The second \( Id(\Sigma^) \) expression shows that subtexts between consecutive elements of \(dom(T)\) (the \(u_i\)’s) are translated via identity. Text parts matching \( Id(\Sigma^*) \) expressions can contain entries from \(dom(T)\), as a consequence, the \(T\)-replacement is always optional.

Figure 3.2: Transducer for the optional rewrite relation induced by T

Let’s process the following text through the optional rewrite transducer.

\[ \underline{ab}ac\underline{bc}a \longmapsto_{R^{opt}(T)} \{ abacbca, dacbca, abacda, dacda \} \]

The transducer will result in 4 successful paths for this text, hence we have 4 different translations. The optional rewrite relation is simple, yet not very practical because realistically we’d rarely want to skip rewrites.

Now, let’s define the obligatory rewrite relation induced by the transducer \(T\) for the rewrite rule \(ab|bc \to d\).

\[ R(T) := N(T) \cdot (T \cdot N(T))^* \]

where \(N(T)\) is the identity function on all strings that do not contain any infix from \(dom(T)\), including \(\{ \langle \epsilon, \epsilon \rangle \}\)

\[ N(T) = Id(\Sigma^* \setminus (\Sigma^* \cdot dom(T) \cdot \Sigma^* )) \cup \{ \langle \epsilon, \epsilon \rangle \} \]

The obligatory rewrite relation \(R(T)\) is also regular, thus we can build the corresponding transducer.

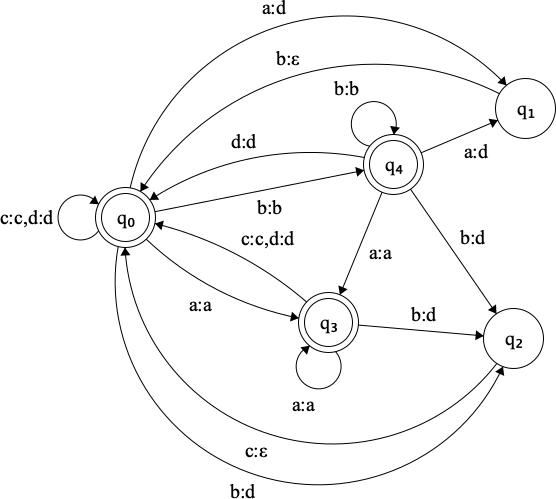

Figure 3.3: Transducer for the obligatory rewrite relation R(T)

This is the result of performing an obligatory rewrite of the text

\[ \underline{ab}ac\underline{bc}a \longmapsto_{R(T)} \{ dacda \} \]

with a state path

\[ q_0 q_1 q_0 q_3 q_0 q_2 q_0 q_3 \]

Rewrite Grammars

In practice, we might want to have multiple rewrite rules. So far we’ve learned that each rewrite rule is a binary regular string relation and that these relations can be represented by finite-state transducers. Suppose we have the rewrite rules

\[ G = \langle R_1, R_2, R_3 \rangle \]

then for each rule, we can construct a corresponding FST

\[ T_1, T_2, T_3 \]

extend each transducer so it can process arbitrary text \(t \in \Sigma^* \) performs obligatory replacement of multiple occurrences of substrings of \(t\) which are in \( dom(T_i) \) ending up with

\[ \langle T_{R(T_1)}, T_{R(T_2)}, T_{R(T_3)} \rangle \]

We build the transducer for the rewrite rule set by composing the transducers for each rule.

\[ T_{R(T_1)} \circ T_{R(T_2)} \circ T_{R(T_3)} \]

Think of it as function composition in programming. The order here matters because the first transducer processes the input text, whereas the rest of the transducers work on the output of the one before them. As a rule of thumb, we should always order the rewrite rules from the most specific to the least specific one. Let’ see an example.

\[ R_1 = ab|bc \to d \\ R_2 = da \to x \]

\( R_1 \) and \( R_2 \) are regular relations from which we construct FSTs for obligatory replacement. The regular relations are closed under composition which means that we can construct a single transducer by composing several transducers. Note that relational composition only makes sense if the alphabet of the second tape of the first transducer coincides with the alphabet of the first tape the second transducer. Now we see how to apply their composition for text rewriting.

\[ (T_{R(T_1)} \circ T_{R(T_2)})(abacbca) \to \\ T_{R(T_2)}(T_{R(T_1)}(abacbca)) \to \\ T_{R(T_2)}(dacda) \to \\ xcx \]

Description of a direct composition algorithm is out of the scope of this article, but you can find some resources in the references.

Conclusion

In this article, looked at the text rewriting problem from a set-theoretic perspective. We learned how the rewrite rules can be represented as regular string relations which on the other hand have an equivalent formalism namely the finite-state transducers. We covered the differences between automata and transducers and saw how the latter can be extended to work on a larger set of inputs via concatenating string relations. We also learned that the transducers can be composed in a single transducer which applies a set of rewrite rules.

Some text can contain conflicting parts. Consider the “abc” and the rule \( ab|bc \to d \). The transducer in Figure 3.3 is not able to make a unanimous decision, thus, it will output both “dc” and “ad”. In the following articles, we’ll discuss some conflict resolution strategies and how to incorporate them within the means of regular sets and relations. We’ll also narrow down the scope and work only with deterministic devices for obligatory text rewriting as they’re more interesting from a practical standpoint.

You can find examples and resources on how to efficiently construct FSTs in the references below.

Part 2: Resolving Ambiguity in Text Rewriting

If you’re interested in formal language theory & language processing, you can check out these articles as well.

References and Further Reading

- Implementation of a Subsetequential Transducer for Dictionary-Based Text Rewriting

- “Direct Construction of Minimal Acyclic Subsequential Transducers” by Mihov & Maurel

- Chapters 4 and 11 of “Finite State Techniques - Automata, Transducers and Bimachines” by Mihov & Schulz

- “N-Way Composition of Weighted Finite-State Transducers” by Allauzen & Mohri

- “Regular Models for Phonological Rule Systems” by Kaplan & Kay

- The graphics are implemented using the Finite State Machine Designer